While I was struggling to adjust to life in the big city, my father was coming unraveled back in Tennessee. My mother had finally left him, forcing the sale of their home in Lawrenceburg and upending Dad’s his life from top to bottom. I don’t think he even argued in his own defense. Rather, he just let her take whatever she wanted, allowed her to set up their soon-to-be-separate finances to her own best benefit, and--at some level--accepted responsibility for destroying her life and his. He raged, sure, when he was drunk, but he never actually defended himself nor stopped loving my mother. For that reason, he let her take advantage of him and of the situation.

Or maybe he was just so drunk that he didn’t notice.

|

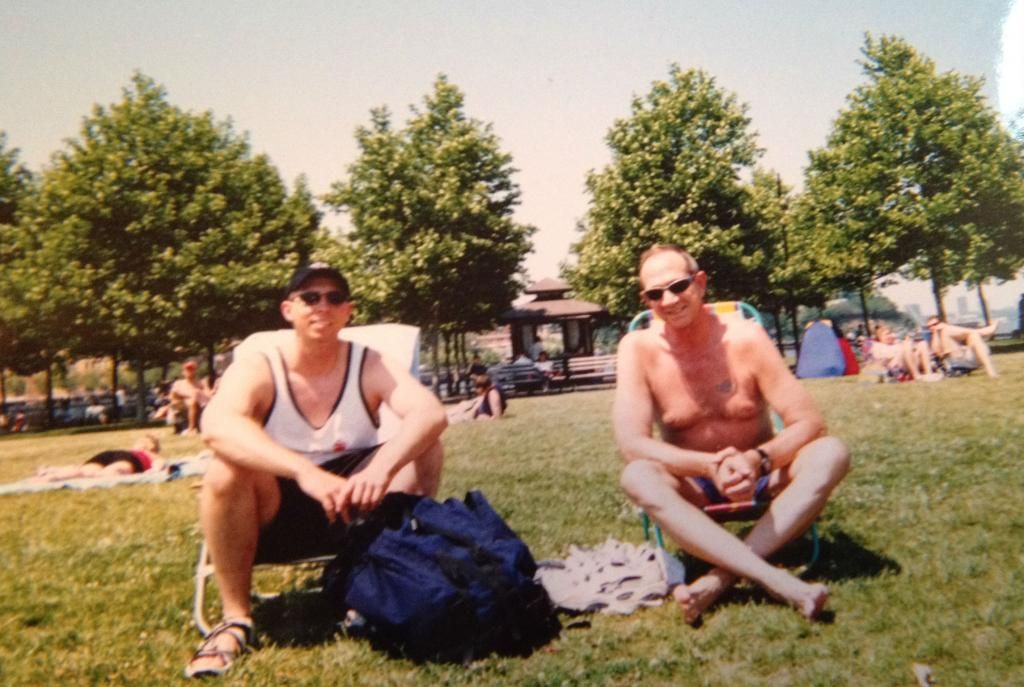

| Me and my dad out at Pier A in Hoboken, Spring 2002. |

Dad wound up living in an apartment in Columbia, Tennessee, a middle-of-nowhere town a few miles south of Nashville. As time went on, he grew increasingly depressed, which both fueled his drinking and brought out his worst, most vindictive impulses. He drifted away, becoming a kind of lost soul. His glory days shined like a beacon in his memories, goading him with what he could be but no longer was. On top of everything, the United States was headed back to war, and my dad, who’d spent his entire lifetime training for exactly this kind of eventuality, was about to miss it. It tore at his mind. He called everybody, but this would be a young man’s war. No one wanted a greybeard colonel whose best days were a decade gone.

My father had lost everything. His wife was gone, he’d been fired from two jobs that had at least provided him with a modicum of dignity and self-respect, his Marine Corps career was truly finished, he’d had cancer, and his only son had moved to New York City. He had a psychiatrist and a prescription for Zoloft, but these things were no match for whatever demons emerged to fill the void in his day-to-day existence.

My father’s beloved Tennessee Volunteers made it to the SEC Championship Game in 2001, but they lost--badly. Dad called me on the telephone immediately after the game, saying, “I’m going to kill myself. I’m going to put on my dress blues and hang myself from a tree in your mother’s front yard. I’ll show that bitch what I think of her! How do you like that?”

I didn’t like it. At all. I sat there staring at the phone for a long moment, aware in a very real way that my own father’s father had, in fact, killed himself. Dad’s dad had also been a drunk. He’d eventually locked himself in his garage with his car running. He’d died from carbon monoxide poisoning, no doubt amidst a drunken rage. He’d done it shortly after my parents had gotten married.

I tried to talk my father down, but there was no reasoning with him. I could hardly understand him, in truth. He was so drunk that his words slurred incomprehensibly, and anyway, he wouldn’t remember our conversation when next we spoke. So I listened until he ran out of steam, and then we hung up.

I got up and paced around my apartment. My father, I knew, had only called me because I was the single person on Earth who was still reliably taking his calls. That didn’t make me qualified to deal with his madness. I sighed and then sat and put my head in my hands.

He’s going to kill himself eventually. Maybe not today, but someday.

I looked up at my ceiling. This is when people say that they throw their problems up to God. Let go and let God. That’s a thing, right?

So I prayed.

Weeks passed, though, and if God was listening, he sure as shit wasn’t doing anything to change my life in concrete terms. Dad didn’t magically get sober. He didn’t stop threatening to kill himself; in fact, those threats came with increasing frequency, though he--thankfully--never seemed to remember most of the fucked up shit that he said when we talked. Eventually, I tried talking to my mom, but she just told me that this was all my fault for moving away.

I got off the phone with my dad maybe two weeks after that first drunken rampage, having again listened to him spout bullshit for an hour or more, and for whatever reason, I decided that I’d had enough. Clearly, God was not going fix it for me. If I wanted to fix things, or to at least take some control back in my own life, I was going to have to do it on my own. I grabbed the Yellow Pages and started looking for an Al-Anon support group. I didn’t find one, but I did find a counselor who specialized in treating families with substance abuse and addiction.

“I want you to know that you’ve found a counsellor who can help,” the woman said when I got her on the phone.

“I’ll believe that when I see it,” I replied.

“But you have to believe that I can help you,” she said, sounding plaintive. “I know I can.”

“Then you shouldn’t have any problem proving it. I don’t take anything on faith. Not anymore.”

* * *

I drove out to that counsellor’s home, which proved to be in Elizabethtown, New Jersey. I soon found myself standing in front of a small two story yellow-brick townhouse. The counsellor turned out to be an older woman, maybe my mother’s age, with graying black hair and a collection of tchotchke knickknacks that might have been at home on my grandmother’s mantel. It felt weird in the extreme sitting in someone else’s living room and laying out my problems in detail to a total stranger, but there I was, no shit. I needed help, and I knew it. There was no way around it.

I made up my mind and sat down, laying it out as succinctly as I could. I ended with, “I just don’t know what to do.”

“Your parents are poison,” the counsellor said when I’d finished. She was not hesitant about it, nor did she seem embarrassed by what she’d heard. “Your folks a sinking ship. You might be a good swimmer, but you’ll never be able to hold that ship up all by yourself. Really, there’s nothing you can do. They’re going down—with or without you. You have to decide if you’re going to get yourself onto a lifeboat, or if you’re going to go down with their ship.

“You have to make a choice. You can either save yourself, or you can get dragged under,” she said. “But the ship is going down. It’s as simple as that.”

So. Maybe not the most uplifting message, but one that I badly needed to hear. Or maybe I just needed somebody to tell me that I wasn’t crazy. That I wasn’t a bad son, or that if I was, at least I had reason to be. In truth, the counsellor never told me anything that I hadn’t first told her myself. Still, there’s no doubt that talking helped. It allowed me to make decisions that I’d needed to make, to wall off certain parts of my life, to realize that I had to take responsibility for my own situation while refusing responsibility for things that were ultimately outside of my control. I had to learn to refuse guilt. I could be angry, but I had to understand my anger, and eventually, I would have to let it go.

“You only get one life,” she said. “There’s no practice run, no ‘waiting until you’re ready’ to be happy. If you ever want to be happy, this right here is your first and only opportunity.”

I did want to be happy. More than that, I wanted to be in control of my own choices.

“Dad,” I said on the phone one night, “I want to have a relationship with you. I do. But I can’t, not unless you’re sober. If you decide to stop drinking, give me a call. You can even come live with me if you want. I’ll be happy to help you get your life back together. But I can’t be around you right now, not if you’re drunk.”

And that was that.

As my counselor said, “Sure, he’s got a disease. He’s like a diabetic who refuses insulin. He won’t help himself. But he could. Alcoholism is one hundred percent treatable, you just have to want to live.”

Dad didn’t. I’d known that. He was a man who’d accomplished so much with his life, so often against overwhelming odds. But he went down hard, and really, he didn’t put up much of a fight.

My mother got angry. She didn’t like that I’d cut my father off, and she especially didn’t like that I started getting my life back together again afterwards. She’d call and talk endlessly about my father or lay on the most self-righteous, unanswerable guilt.

“Why don’t you love me?” she’d ask viciously. “Was I such a terrible mother that you want to cut me completely out of your life? Why do you hate me so much?”

“I don’t hate you, Mom.”

“Then why did you marry Misty? Why did you move away? Why won’t you come home and help me take care of your father? Was I really such a terrible mother that you just can’t stand to be around me at all?”

It was a mistake even to attempt to engage. Answering the unanswerable was a fool’s errand. Instead, I learned to describe my mother in terms generally reserved for nuclear weapons. My minimum safe standoff was about thousand miles.

No comments:

Post a Comment