“Cut off as I am, it is inevitable that I should sometimes feel like a shadow walking in a shadowy world. When this happens I ask to be taken to New York City. Always I return home weary but I have the comforting certainty that mankind is real flesh and I myself am not a dream.”

― Helen Keller, Midstream: My Later Life

I spent two weeks in temporary corporate housing while I familiarized myself with my new home. They put me up in Jersey City, New Jersey, down by the PATH station near the banks of the Hudson River. From there, I spent time exploring various parts of Manhattan and trying to decide where to live. I toured Trump Tower, decided it was far too expensive for what it offered, and finally settled on a one-bedroom basement apartment in a brownstone in Hoboken. My landlord turned out to be the local judge. Her husband was a powerful corporate attorney working out of an office in Manhattan.

|

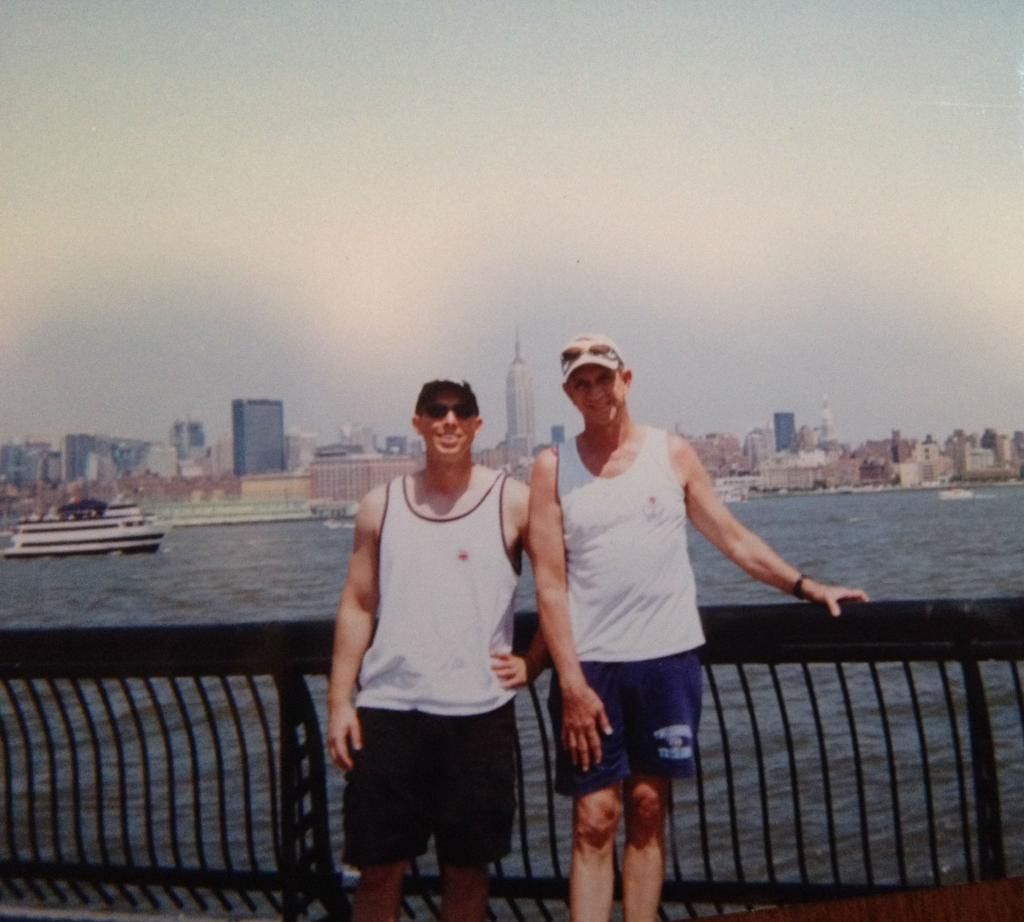

| Me and my dad on a run in Hoboken, 2002. |

Hoboken seemed a dream come true. Nicknamed “The Mile Square,” by August 2001 it had become the hyper-urban Northeast’s answer to small town America. Tree-lined streets branched at perfect right angles off an old-fashioned main street, called Washington Street, which lay at the town’s heart. Washington Street was bookended at either end by gorgeous public parks carved from city squares reminiscent of those in Savannah, Georgia, or reclaimed from the wreckage of industrial wharfs left over from the town’s industrial portside past. The largest of these was Pier A, an enormous grassy expanse on the town’s south side that stuck boldly out into the Hudson River. Nearby, several large public playgrounds and ball fields spoke to the town’s desire to support growing young families.

Though upscale midrise apartment buildings had begun to sprout along Hoboken’s waterfront, small businesses fronted most of Washington Street and many of the town’s side streets as well. The town itself, however, was still centered around its traditional, brick brownstone townhouses and one-time tenement apartment buildings. The majority of these had been refurbished in the early years of New York City’s economic revitalization, turning Hoboken into a magnet for young, upwardly mobile newcomers. Neat urban streetscapes teemed with junior professionals, giving the streets a pulse of excitement.

I was shocked by the price of rents—by the price of everything—but I was also earning twice what I’d made as an Army captain. Even my layoff worked out as a net positive. I’d gotten almost fifteen percent more from my new employer than I’d been making with KSA, though the loss of my expense account lifestyle reduced my real finances somewhat more dramatically than I’d expected. I could afford New York’s suburbs, it turned out, but not in the same way that I’d been able to afford Munson, South Korea, or Lawrenceburg, Tennessee. My new home was a whole new world, one I would have to learn to navigate almost from scratch.

My household belongings arrived around the first of September, and I set about moving in. I bought a big green fold-out futon couch from a local place on Washington Street and found myself taking a series of mandatory safety and environmental classes at my company’s gorgeous corporate learning facility, located on the East River in Queens just across from the United Nations. I saw the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center regularly from both the park at Pier A in Hoboken and from the banks of the East River in Long Island City. New York’s skyline fascinated me, and though my buddy Dave and I had been to the top of the Empire State Building as cadets, I’d never been to Windows on the World, the restaurant at the Trade Center’s apex. I resolved to get a reservation and to figure out who I could take on a dinner date.

By September 11, 2001, I’d been in town for a bit more than a month. I’d made a few friends at work and had reconnected with an old high school acquaintance, but I’d not yet established myself. I’d found New Yorkers friendly but aloof. They were happy enough to talk on the street, and this marked a dramatic improvement from what I’d experienced in Lawrenceburg, Tennessee, but most folks weren’t necessarily looking for a new best friend. That made sense in a city of eight million, but it also made finding a new social scene difficult. My work colleagues were happy enough to meet, but they were spread across the five boroughs of New York plus Westchester County, making the logistics of nights on the town more challenging than I’d anticipated. I missed the manly camaraderie of Camp Garryowen, even if I much preferred the cityscapes of Manhattan to the forlorn rice paddies of rural South Korea.

It would work itself out in time, I was sure. I joined a gym, found a favorite local bar, and made an effort to spend as much time as possible exploring my new hometown.

September 11th began as perhaps the nicest day I’d ever seen. Late spring and early fall are the best times to be in New York, and that day in particular dawned to perfection. The morning saw seventy degree weather beneath crystal blue skies, cloudless with the sun just warm enough to kiss my skin and make me feel alive. Though my primary office was located in Westchester County, I was back in Queens that day for a class on technical drawings and design schematics. We broke for coffee around nine, and I headed out to the Learning Center’s back deck. A colleague and I started talking. I let myself turn to face the United Nations while the sun shone fully across my back.

“Holy shit! What the Hell was that?!”

“I think some asshole just flew a plane into the side of the World Trade Center.”

“What kind of plane was it?”

“I don’t know. Might’ve been a Cessna. What an idiot!”

I turned and saw a smoking crater in the side of one of the Twin Towers. We started talking, wondered how in Hell some dumbass could possibly have gotten that far off course, and then another plane banked and slammed head-on into the other tower.

“Oh my God,” I muttered. “That couldn’t have been an accident. That was an attack!”

My colleagues and I watched in helpless horror as the morning’s events unfolded. Police cars and fire trucks jammed the FDR Drive as far as the eye could see, their sirens echoing endlessly across the East River. Smoke poured from the towers, and after an hour or so they collapsed, leaving a literal mountain of smoke billowing up more than a thousand feet into the air.

I saw my boss in the parking lot and asked him what I should do. Our company had extensive facilities in the basement of the Trade Center. Whatever else happened, we’d be heavily involved in the recovery effort.

“I don’t know,” my boss told me. He shrugged and looked helpless. “Just go home and stay safe. For now, you’d just be in the way.”

I walked back towards the parking lot, feeling useless and shell-shocked, unsure what the future held. Unbidden, my tactical training informed me that this would be the time to bomb the casevac procedures, that a car bomb or some other follow-on attack would cripple the recovery efforts and leave the city panicked for weeks or maybe even months to come. Thankfully, that kind of sophisticated tactical planning never materialized.

I found a few of my fellow new-hires waiting by their cars. “What now?”

My friend Nick shook his head. “They just closed all the bridges and tunnels and shut down the subways. We’re not going anywhere.”

Shit, I thought. I had to cross two rivers to get back to my apartment. It seemed a small concern, but in the chaos of the moment, the last thing I wanted was to be stuck on the wrong side of the City until God-knew when.

“Come on,” Nick said at last. “I know a place a few blocks from here.”

We walked down a half dozen or so blocks to find a corner pub with a long wooden bar. The pub was fronted by a series of glass-paneled French doors, now open to let in the late morning air. Working professionals sat or stood hovering inside, either staring at the television or speculating in low tones about what the attacks portended for the future. I ordered a beer and sat on one of the empty stools, not so much drinking as simply trying to be in the company of other people.

“Do you think they’ll recall you to the Army?” Nick asked.

Having spent a full year trying to establish myself in the civilian world, the idea of returning to uniform was not particularly appealing. I was sure that the men who decided on assignments would look upon my time out of service as proof of my lack of faith. They’d never put me back on a tank. I’d be stuck with whatever shit jobs they had leftover, riding a desk or doing some other bullshit so the True Believers could go and fight. Beyond that, who knew what the response was going to be or whether it would be well-reasoned enough to address the actual issues at hand?

“I don’t know,” I said at last.

“What do you want?”

“I don’t know that, either.” I shrugged. “I’ll do what I have to, I guess.”

We sat at the bar for another hour, talking to strangers and trying to make sense of what we’d just seen. There was no sense to be made. I realized in time that I would either have to hit the road and try to make it back to New Jersey, or I would wind up sleeping in my car in a parking lot in Queens. Were I still in the Army, a buddy would have offered his couch. No such offers were forthcoming from the civilians of New York City, however, not even in the wake of a terrorist attack. Besides, I had neither a toothbrush nor a change of clothes, and I needed to travel less than ten miles to get home. I had to be at work the next morning and might potentially be involved in the clean-up soon afterwards. I would do well to get right before all of that started.

How bad could the drive home be?

Bad. It took me two hours to get out of Queens and another four to get across the Cross Bronx Expressway, only to discover that the George Washington Bridge remained closed. I headed north reluctantly, relying on surface streets and trying to come up with another plan. Recalling my days at the Academy, I eventually hit Route 9, discovered that the Tappan Zee Bridge was also closed, and drove even further north, all the way up to Bear Mountain. New York State police waved me across the Bear Mountain Bridge, and I then drove back south on the Palisades, eventually getting in touch with my parents for the first time since the attacks.

No, I told them, I wasn’t leaving New York. No, I didn’t know what would happen next.

No comments:

Post a Comment